- An 8-year-old boy with Asperger’s Syndrome is suspended from his elementary school after getting frustrated in class and balling his fist around his pencil, an action that the school called “aggressive.”

- A 10-year-old boy with emotional and behavioral disabilities is harassed by fellow students and reports regular incidences of bullying to school administrators, but the bullying continues. When he finally jumps to his feet and screams, “I could kill you,” the police are called to school, and he is handcuffed and arrested for making terroristic threats.

- A 15-year-old girl with disabilities is asked to leave the classroom for using her cell phone. When she refuses, the police are called. She pulls away when the officer tries to forcibly remove her. She is pepper-sprayed; taken down; arrested; and charged with trespassing, assault on a law enforcement officer, and resisting arrest.

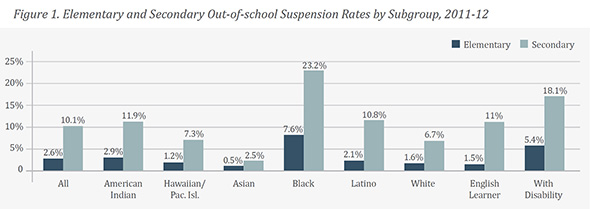

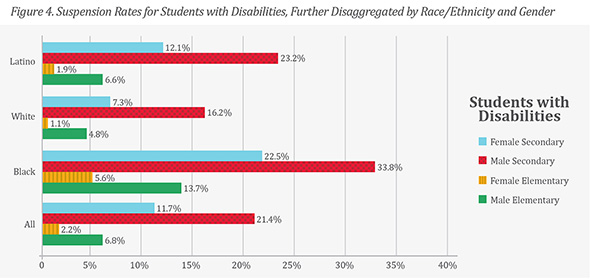

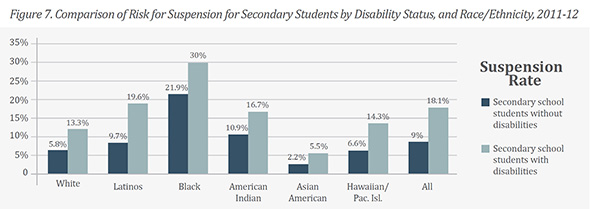

A sweeping new study by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA1 shows that nearly 1 in 5 students with disabilities were given out-of-school suspensions during the 2011-2012 school year, a rate two to three times that of typically developing students. The nationwide study examined out-of-school suspension rates at state and local district levels, and it reveals that suspension rates vary widely both by state and by districts within states.

A sweeping new study by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA1 shows that nearly 1 in 5 students with disabilities were given out-of-school suspensions during the 2011-2012 school year, a rate two to three times that of typically developing students. The nationwide study examined out-of-school suspension rates at state and local district levels, and it reveals that suspension rates vary widely both by state and by districts within states.

The study also analyzed the suspension cohort by race/ethnicity, gender, and grade level. Here, too, there were significant disparities. The highest of these were for African Americans, males, and secondary students.

The study explicitly questions whether students with disabilities are being taken out of class unlawfully due to behavior issues related to their disabilities.

Local Practice Drives Variability

The radical variability among suspension rates between districts is a pattern that is seen nationwide. Studies have shown that much of what determines whether a school is higher or lower in suspending is directly influenced by its local school leaders.2 Most large districts show important variation in suspension rates from one school to the next. One study in Texas that tracked middle school students in Texas—controlling for race, poverty, and district policy—showed that school-level factors had the most important impact on suspension rates. A separate statewide study in Indiana found that after controlling for race, poverty, and other factors, the single most important predictor of suspension rates and disparities in suspension rates is the school principal’s attitudes toward the use of harsh discipline.

Zero Tolerance

Zero-tolerance policies gained popularity in the 1980s during the US government’s “War on Drugs,” along with efforts to stem urban violence. By the early 1990s, school systems began to adopt zero-tolerance policies to address drug, weapons, violence, smoking, and school disruption in efforts to protect all students’ safety and maintain a school environment that is conducive to learning. Such district-wide policies often prescribe harsh consequences or punishments, such as suspension and expulsion.

In 1997, IDEA was amended to support students with disabilities who exhibit challenging behaviors. The amendments required the consideration of “positive behavior interventions, strategies and supports” when a student’s behavior “impedes his or her own learning or that of others.” The practice of conducting “manifestation determinations” — a sequential and structured approach to determining whether a student’s interfering behaviors were caused by his/her disability — was required.

By the turn of the century, over three-quarters of our nation’s schools were reporting that they had zero-tolerance policies in place. Suspension was the most frequently reported punishment for a wide range of common offenses, including less egregious infractions like attendance problems, disrespect, and noncompliance.

Zero-tolerance policies are still being used widely under the assumption that consistently removing disruptive students would deter other students from similar conduct while simultaneously enhancing the climate of the classroom.

But research and experience don’t support that assumption — neither for students with disabilities nor their typically developing peers. In fact, there appears to be no relationship between the frequency of students’ removal from school and how “peaceful” or “safe” any particular school is.3 There is also no evidence that the adoption and implementation of zero-tolerance policies has increased the consistency of school discipline. Indeed, the skewed application, variability, and apparent unfairness in suspension data would seem to contradict any claim that zero-tolerance policies engender the consistent application of discipline. Not only is suspension not helping — it is actually hurting. Research indicates that school suspension in general predicts higher future rates of misbehavior and further suspensions for the individual student.4

Despite this evidence, we see no recent decrease in the rate or inequitable application of disciplinary suspensions in schools.

The recent solution of increasing the presence of police (school resource officers) in schools is not supported by evidence. A 2011 longitudinal study found “no evidence suggesting that [school resource officers] or other sworn law-enforcement officers contribute to school safety. That is, for no crime type was an increase in the presence of police significantly related to decreased crime rates. The preponderance of evidence suggests that, to the contrary, more crimes involving weapons possession and drugs are recorded in schools that add police officers than in similar schools that do not.”5

The recent solution of increasing the presence of police (school resource officers) in schools is not supported by evidence. A 2011 longitudinal study found “no evidence suggesting that [school resource officers] or other sworn law-enforcement officers contribute to school safety. That is, for no crime type was an increase in the presence of police significantly related to decreased crime rates. The preponderance of evidence suggests that, to the contrary, more crimes involving weapons possession and drugs are recorded in schools that add police officers than in similar schools that do not.”5

In 2014, the US Departments of Education and Justice released a broad school discipline guidance package to enhance school climate and improve school discipline policies and practices. While school violence has been steadily decreasing for more than 20 years, the guidance was issued in recognition that many schools are still struggling to create positive safe environments, and many students are still missing class time owing to exclusionary suspensions—some for minor infractions of school rules—with students with disabilities and of color disproportionately impacted. For more information on the USDOE and USDOJ Guidance Package, visit the USDOE website at http://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/school-discipline/index.html.

Resources/References

(1) Losen, D., Hodson, C., Keith, M.A., Morrison, K., & Belway, S. (2015). Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap? The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at The Civil Rights Project. University of California Los Angeles.

(2) Skiba, R.J., Cunk, C.G., Trachok, M., Baker, T., Sheya, A., & Hughes, R. (2015). Where should we intervene? Contributions of behavior, students and school characteristics to out-of-school suspension. In Losen, D.J. (Ed.) Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion. New York: Teachers College Press.

(3) Bickel, F., & Qualls, R. (1980). The impact of school climate on suspension rates in the Jefferson County Public Schools. Urban Review, 12, 79 – 86.

(4) Costenbader, V., & Markson, S. (1998). School suspension: A study with secondary school students. Journal of School Psychology, 36, 59-82. Similar results found in Bowditch, C. (1993). Getting rid of troublemakers: High school disciplinary procedures and the production of dropouts.

(5) Na, C. and Gottfredson, D. (2011). Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offending Behaviors. Justice Quarterly, pp1-32; Similar results found in this study: Jennings, W. G.; Khey, D. N.; Maskaly, J.; & Donner, C. (2011). Evaluating the Relationship between Law Enforcement and School Security Measures and Violent Crime in Schools. Journal of Police Negotiations 11(2):109-124.