There are many things that can cause or prompt challenging behavior in a student with disabilities. Recognizing that behavior may be rooted in prior traumatic experience can help educators develop effective responses that not only reduce unwanted behavior, but also support the student in recovery and growth.

This approach to behavior and learning readiness, often called Trauma Informed Care (TIC), is gaining a foothold in schools and classrooms nationwide.

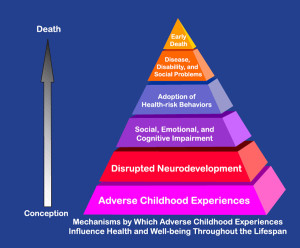

There are two reasons for this shift. First, while educators have long recognized that trauma can interfere with a student’s ability to learn, it was thought to be a smaller problem than it is. New research, conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente’s Health Appraisal Clinic reveals an alarming frequency of exposure to traumatic childhood experiences, that cuts across socio-economic status, race, age and gender.

The data suggest that childhood trauma is more wide-spread than previously thought, and presents significant risk factors for childhood development, and lifelong health and well-being.

The data suggest that childhood trauma is more wide-spread than previously thought, and presents significant risk factors for childhood development, and lifelong health and well-being.

A second reason for the emerging movement towards Trauma Informed Care is the growing recognition that school-based Zero-Tolerance approaches to behavior are not effectively reducing the incidence of interfering behavior, and, in fact, may be further traumatizing the students on whom it is exercised.

Child Traumatic Stress

Child traumatic stress occurs when children and adolescents are exposed to traumatic events or traumatic situations that overwhelm their ability to cope.1

While some children may “bounce back” after adversity, many traumatic experiences — especially repeated trauma – result in a significant disruption in development and can have profound long-term consequences.

Some types of traumatic events involve:

- experiencing a serious injury, or witnessing a serious injury or death.

- facing imminent threats of serious injury or death to one’ self or others.

- experiencing a violation of personal physical integrity.

These experiences usually call forth overwhelming feelings of terror, horror, or helplessness. These short-lived,acute traumatic events might include:

- School shootings

- Gang-related violence in the community

- Terrorist attacks

- Natural disasters (i.e., earthquakes, floods, or hurricanes)

- Serious accidents (i.e.,car or motorcycle crashes)

- Sudden or violent loss of a loved one

- Physical or sexual assault (i.e.,being beaten, shot, or raped)

Exposure to trauma can also occur repeatedly, over long periods of time. These experiences call forth a range of responses, including intense feelings of fear, loss of trust in others, decreased sense of personal safety, guilt, and shame. Such chronic traumatic situations might include:

- Some forms of physical abuse

- Long-standing sexual abuse

- Domestic violence

- Wars and other forms of political violence

- Refugee status

Adapted from Defining Trauma and Child Traumatic Stress, at The National Childhood Traumatic Stress Network.

Trauma can impair the development of a student’s ability to regulate emotions and to control impulsive and externalized behavior. Reactions can be triggered in any setting — including the classroom — if the student feels provoked or if something reminds them of their trauma. For the child who has been traumatized, common classroom interactions may be experienced as very threatening, and the student’s response may seem out of proportion with the situation to the uninformed observer. The traumatized student will express toxic stress in the same way that any individual would: fight, flight, or freeze. Trauma and stress rewire the brain. The experience of toxic stress makes it physiologically impossible to learn.

Traumatized children may show behaviors such as aggression, defiance, avoidance, instructional interruption, excessive impulsivity, and more. It is easy for the classroom teacher to misinterpret such behavior as intentional, but when behavior is rooted in trauma, a child’s brain and central nervous system have been rewired. Research has suggested that chronic stress and trauma cause long-lasting changes in specific brain regions and the central nervous system, resulting in changes in brain “circuits,” involved in the stress response. Neurochemical and hormonal responses then become exaggerated, and can cause unmediated fear responses, prompting significant alterations to memory, dissociative amnesia, and arrested development in some regions of the brain.2

Becoming a Trauma Informed School

Children who have been traumatized need support and understanding from those around them. Because trauma survivors can be re-traumatized by well-meaning teachers and schools, understanding the impact of trauma is an important first step in becoming a compassionate and supportive community. A trauma-informed approach may be developed at the school or organizational level, separate and distinct from any student-specific interventions or treatments.

According to the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a system that is trauma-informed:

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery;

- Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system;

- Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and

- Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.

In order to move toward a trauma-informed approach, SAMHSA recommends adherence to six key principles:

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and Transparency

- Peer support

- Collaboration and mutuality

- Empowerment, voice and choice

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues

TIC schools also promote linkages to recovery and resilience for those individuals and families impacted by trauma, and provide services that build on the best evidence available and consumer and family engagement, empowerment, and collaboration.

A TIC school will implement programs and interventions that reflect the relationship between trauma and symptoms of trauma such as substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, and anxiety. TIC schools work in a collaborative way with survivors, family and friends of the survivor, and other human services agencies in a manner that will empower survivors and consumers; and they honor the survivor’s need to be respected, informed, connected, and hopeful regarding their own recovery.

Benefits of Becoming a TIC School

Schools and teachers are themselves stressed, so becoming trauma informed may seem to be a challenging strategy. While a TIC approach requires a paradigm shift for some schools, the cost can be minimal, and the benefits3 crosscutting:

- Improved academic achievement and test scores

- Improved school climate

- Improved teacher sense of satisfaction and safety in being a teacher

- Improved retention of new teachers

- Reduction of student behavioral out-burst and referrals to the office

- Reduction of stress for staff and students

- Reduction in absences, detentions, and suspensions

- Reduction in student bullying and harassment

- Reduction in the need for special educational services/classes

- Reduction in drop-outs

Resources for Educators

- Trauma Informed Care Project – Resources for Schools

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network – Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators

- Trauma Informed Care Project – Preparing and Creating an Action Plan

Footnotes:

- Definition as used by The National Childhood Traumatic Stress Network.

- Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2006 Dec; 8(4): 445–461. J. Douglas Bremner, MD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain.

- Trauma and Loss: Research and Intervention. 2008 8(2), Barbara Oehlberg, LCSW. Adapted from her article Why Schools Need to be Trauma Informed. Available online as PDF at The Trauma Informed Care Project.